On board the Pelican, being served breakfast with the wall mounted speaker conveying music and news in French. My French was sufficient to understand the breaking news. 27th March 1980. An oil rig had totally capsized in the North Sea. Disaster, but there were many oil rigs in the North Sea.

Then the oil rig was named – the Alexander Kielland. My rig.

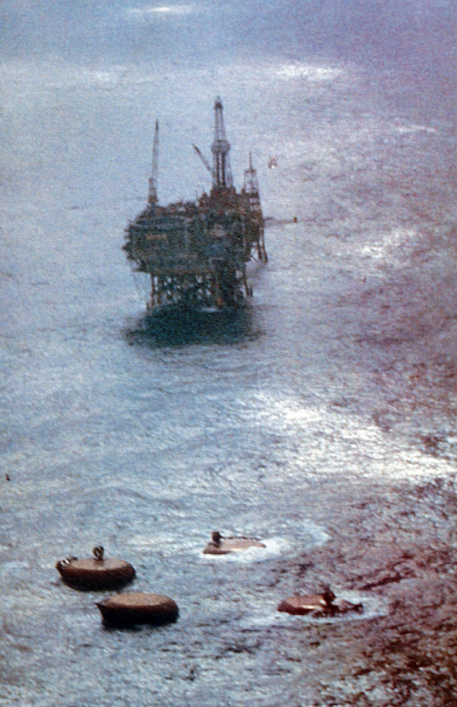

The one I was based on only three weeks ago just before my transfer to Spain. If I was still in Norway I would have been on it. A chill came over me as I remembered the five-storey high accommodation units stacked on the deck of the exploration rig to turn it into a ‘flotel’ – a floating hotel. Now that was marketing poetic license.

The tall drilling derrek hadn’t even been removed, making the Kielland top heavy and slow to right itself in a big sea. I hated sleeping on it.

Everyone had to cross a bridge with a sliding gangway to get to the actual oil platform where we worked. Okay in a calm sea but with wind and a swell it was scary.

I imagined the crowds of men trying to get into lifeboats or just get outside during the 14 minutes before the Kielland went from a 30 degree list to full capsize. You had to step into a room to let someone else pass by, the corridors were so narrow. Our company had a crew on board (it would’ve been me and my operators) and I knew at least one who was plucked out of the sea.

In total 123 men died that night.

I know I felt survivors’ guilt for weeks after the tragedy. The newspapers covered the aftermath and eventual towing the rig into a fjord to recover the bodies. I was the only one on the French drilling ship directly connected to the awful tragedy. It was just another distant event to all the other men getting on with their work.

I will not describe now any further this disaster, but with present day internet search it is possible to fully research the sacrifice these men made to help give us the energy source we still all depend on. Recent 2019 YouTube video produced by the Norwegian Safety Authority https://youtu.be/KmbLvzPMuRI

Perhaps even though I was still in my 20s I was becoming more aware of my own mortality. Expose yourself endlessly to a dangerous environment and one day it could bite you.

It was time to move on in my engineering career – something more stable and safe.

I thought over the possibilities. I realised there was only one thing to do- it was time to resign.

I telephoned headquarters in London UK, explained the situation and offered my resignation.

“Give us a couple of days and we’ll get back to you.”

I assumed they would be scrambling to line up my replacement but when the call came it was to offer me a post anywhere in the world!

They valued me after all.

It was such a generous offer. USA, Africa, Far East, Australia, we operated anywhere there was oil or gas.

But it was too late – overloaded, overstressed and tired of the unpredictable hours I thanked them for the suggestion but held to my resignation.

“What about running logs for the National Coal Board in the UK until you decide what’s next? No more helicopters, all daytime work. Home every night.”

“Yes okay that sounds a good idea, I’ll go for that.”

“Leave it with us,John. We will be in touch.”

Recounting this episode to a French engineer he decided he wanted a more exotic foreign posting too.

“I shall call and offer my resignation, as you did.”

“Look, it’s not automatic to get a better posting. Make sure you mean what you say.”

He did phone London to resign. When their call came back a few days later it was to request he put his resignation in writing.

As for me- the company base in Walsall, Birmingham, England was soon my new exotic location.